Phenomenological Complexity Classes

This is an introduction to phenomenological complexity classes. The formulation is my own, but is heavily informed by existing results in developmental psychology and complexity theory and parallels phenomenological complexity theory enough that I had to reinvent many aspects of it from the fragments of phenomenology I knew before I started on this project. As such I am working in the field of phenomenological complexity theory ex post facto, so I’ll first explain the history of the idea as I discovered it before formally introducing it and giving an accounting of known phenomenological complexity classes.

The Story of Phenomenological Complexity Classes

For the last few years I’ve been wrestling with an idea. An idea whose threads I found woven through the fields of developmental psychology, phenomenology, epistemology, organizational development, economics, history, information theory, theory of computation, literature, and self-help. I’ve struggled to understand it, and of late I’ve focused my philosophical work on sewing together its many patches of insight into whole cloth. My stitching is still a bit rough, but after long hours of needling, I’m satisfied that my intellectual tapestry can tell its story well enough to be understood.

The seed of the idea formed in me when I was 18. Throughout my junior and senior years of high school I was on something of a quest to find a “true” and “authentic” way to live my life. I tried on libertarianism, Objectivism, classical rationality, pop Stoicism, and more. I constructed for myself a complete worldview out of each, only to inevitably tear each one down when, after a few months, I ran into evidence and arguments that knocked over my reasoning as quickly as a breeze collapses a house of cards. It was during one of these demolition phases, before new building had begun, that I had an epiphany.

I was reading, of all things, Eliezer Yudkowsky’s Creating Friendly AI. I seriously doubt that CFAI has any special power to do this, but in the midst of reading Chapter 2, my relationship to reality changed. I realized that all my creating and destroying of worldviews had been attempts, not to understand reality, but to try to make reality as I wanted it. When I looked at libertarianism and the rest it hadn’t been that I thought they offered a way to live the kind of life I wanted to live, but instead that I thought that through them I could organize the universe to make it behave the way I wanted it to. But the universe keeps its course no matter how we think of it, and coming face-to-face with my mistake, for the first time I chose to engage with reality rather than hide in my perception of it.

My reason for telling this story isn’t to share this particular insight, which I hope is so obvious as to seem banal. What’s important is that this was the first time I experienced my mind shifting from one way of thinking to another. Something in the character of my thought changed that day, and though it took years to solidify and really stick, it set me down the path to discovering that understanding can change not just in amount but in kind.

But one event does not a pattern make, so I needed a second hard striking with the clue bat to see the outline of the big idea. I had to wait 11 years, and in that time I earned a master’s degree, got married, had a nervous breakdown, took care of my sick wife, got a “real” job, watched my wife lose her job, went broke, defended a dissertation, and then failed out of a math Ph.D. anyway. It was during that ill-fated doctoral career that I learned a lot of decision and game theory, and the more I understood about Newcomb problems and Schelling points, the more decision theory seeped into my soul. Eventually I could see nearly everything through the lens of decision theory, down to the level of mundane activities like negotiating traffic on my daily commute.

So it’s perhaps unsurprising that one day I was in the shower, mulling over my general unhappiness with life at the time, when it suddenly struck me that I could use my knowledge of decision theory to be happier. And what it specifically suggested was that my marriage, which was my primary source of unhappiness, was no longer worth the emotional cost I was paying for it, and I should choose different. So I cried, because in that moment I accepted into my heart that I was the agent of my decisions, and I would have to do things that my attachments and fears were screaming desperately for me not to but which knew I would have to do if I wanted to be happy.

So again my thinking had changed in kind. I went from seeing the world as something external that I could understand to something that I could actively engage with using my understanding. Again that may sound obvious and trivial, but in some real sense I wasn’t doing that before, and getting there required a shift in paradigm.

This made me suspicious that something more was going on than simply changing during the course of my life. Sure, I was maturing, but the nature of that maturation was more complex than I had been lead to believe it would be. It was not simply that more experience gradually lead to more wisdom, but instead that there seemed to be definite milestones a person could pass that opened new ways of seeing that were previously closed to them. I could see in my past self and in those around me that some people had access to more complete world views than others, and those whose thoughts encompassed more were better able to live the lives they wanted to live. To put it another way, it was not just my thinking that changed, but my way of thinking — my meta-thoughts — that expanded to let me think things I could never have thought before.

I again had to wait to make more progress on seeing the idea. It took almost two years from the date of my shower epiphany for me to work up the courage to tell my wife I wanted a divorce, and that only happened because I found myself backed into a corner with little choice but to confess. But cowardice or no, I made my choice, and this, along with changing job prospects, lead me to move to the San Francisco Bay Area in Fall of 2013, where our story continues.

It was August, 2014. I was at a house party in Berkeley, where our idea of a party is one part carousing, one part philosophizing, and one part naked hot tubbing. Between drinks and whirl jets, I stayed up till sunrise with Malcolm Ocean and Ethan Dickinson as they told me about the work of Robert Kegan. I was riveted. Kegan, along with Lisa Lahey, had built a framework for approaching human psychology that encompassed and explained the psychological development I had noticed in myself first when reading CFAI and later when I decided to end my marriage. Their ideas gave me a structure in which to understand why I had experienced these changes, why they were so profound for me, and also why I had such difficulty explaining what had changed in me to others.

This was the last piece of the puzzle I needed, but I had to spend a couple years working through the details so that I could deeply understand it. I read Kegan’s The Evolving Self and In Over our Heads, and with each chapter I checked the ideas against my experiences and the reported experiences of others, referenced the cited books and papers, and worked out the implications of the ideas into new areas. I revisited my conceptions of human behavior to see if and how they fit with Kegan’s theory, and I tested what I discovered on myself, my friends, and my coworkers to predict, explain, and change behavior. I came out of it a dedicated student of developmental psychology.

I wrote a blog for a while where I explored the lessons of mastering the earlier stages of development and how to transition between stages. I gave up this work when I tried to discuss the later transitions, though, realizing I needed more powerful tools to explain myself. Kegan and Lahey’s work on immunity to change was influential, and from there I dove into self-help literature to see how others had approached similar issues in the past. I even tried to write a self-help book and find ways to operationalize my understanding of adult development so that it could help others in a very short lived career as aspiring life coach.

Through this work I distilled my advice for producing the same kind of psychological development in others that I had experienced in myself down to a single phrase: act into fear and abandon all hope. And in the process I had used Daoist philosophy as a scaffold to help me integrate my understanding of Kegan along the same lines as David Chapman has used Buddhism, and as a result generated a “complete” world view similar in tone to the philosophical views of Heidegger and Sartre. My ideas remained nebulous, though, until Robin Hanson asked for people to trade engagement in neglected ideas, and Robin made it clear no such trade would be possible so long as my neglected idea — what I now call phenomenological complexity classes — was both unnamed and explained to others only by reading and thinking about the same material as I had read and thought about.

To my surprise, when I looked for a concise description, I now had one! Thus, this.

Be forewarned, though: the following takes a semi-academic approach as necessitated by the subject matter and is decidedly not light reading. The links are often citations and sometimes point to huge concept masses you may need familiarity with to appreciate the examples. I’ve done my best to keep the philosophical arguments self-contained, but even there the background is considerably larger than I have space to cover. A full presentation of phenomenological complexity classes would likely require a book, so I offer you my thanks in advance if you’re willing to struggle through to the end. I think it’s worth it.

Introduction to Phenomenological Complexity Classes

Phenomenology is an approach to philosophy that primarily concerns itself with experience. It in particular assumes experience is intentional, which is a somewhat confusing way of saying there’s something, a subject, that has experiences of things, called objects, and there’s no way to talk about experience that is not in the context of a subject experiencing an object. The approaches to phenomenology are varied, but here we will take the existentialist view that existence is prior to experience and experience is prior to essence, by which we mean that subjects and objects really exist, that by existing subjects are able to experience objects through causality, and that through experience ontology (the structure of the universe) can be known.

When a subject makes itself the object of experience, viz. the subject experiences itself, the experience is termed consciousness. This is an intentionally broad way of thinking about experience and consciousness so that we can talk about the “experiences” of rocks and the “consciousnesses” of trees. The terminology sounds strange because phenomenology was discovered by thinking about the human experience of self before being generalized, but it is perhaps no stranger than when physicists use “observe” to talk about causality transferring information, and in fact a phenomenological approach to physics would view “experience” and “observation” as one and the same. Luckily, engineers have given us a less anthropomorphic term for consciousness — feedback — and the recognition that consciousness/feedback is widespread lead in the mid-20th century to the establishment of cybernetics as an interdisciplinary field of study over control systems, computation, psychology, politics, economics, and more.

It’s from cybernetics that we can begin to ask “if nearly everything is conscious, what makes a person different from a clock?” since existing phenomenology, even the phenomenology of complex systems, does little to address this question directly. Building on the work of earlier cyberneticists like Bateson, Wiener, and von Neumann, Douglas Hofstadter explored the boundary between the experiences of “mechanical” and “living” control systems first in Gödel, Escher, and Bach and later in I am a Strange Loop. Independently, Kegan wrote The Evolving Self to explain how phenomenological experience develops in humans from childhood to middle-age, and he overlaps with Hofstadter in examining the core qualities of what it feels like to be conscious. Unfortunately, even if we mash their works together, we don’t get a fully integrated approach to the qualitative differences that appear to exist between “mechanical”, “living”, child, and adult because, while Hofstadter addresses cybernetic systems generally, he stops with humans as a category, and Kegan’s work ignores cybernetic systems that are not humans, giving us no extension of his theory that might apply outside psychology. So we’ll have to flesh out the details ourselves, and we can do that by looking at the underlying theme both believe to be the source of qualitative differences in experience: complexity.

Complexity is, roughly speaking, a measure of how difficult it is to do something. In everyday speech we say things like “the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a complex topic” or “cars are more complex than skateboards” to mean “there are a lot of things to consider with regards to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” and “it’ll take a lot more words to describe how a car works than to describe how a skateboard works”. These notions are formalized in computer science and information theory, where complexity refers both to Kolmogorov complexity, defined as the length of the shortest possible description of a string of symbols, and computational complexity, a related notion about the simplest program that can complete some specified task. Extending this concept to other cybernetic systems — phenomenologically conscious subjects — we can similarly talk about phenomenological complexity as the simplest way in which a subject experiences an object.

To begin examining the complexity of the phenomenological {subject, experience, object} tuple, we must have a grasp on what counts as a subject. As it happens, basically everything you can think of counts as a conscious subject in phenomenological terms, from quarks to humans. This is because, from the perspective of intentionality, the only things in physics that might precede experience are vectors in state space and only for so long as you don’t have causality so that one vector can transition to another. As soon as you introduce causality each vector can experience the vectors that came “before” it and they become subjects with their “past selves” as objects that are experienced through the information transferred to them via causality. And since even quarks and other still-developing theories of fundamental stuff are already operating above this level by talking about paths through state space — things — we’re forced to accept that everything in our current models of reality experiences feedback in the cybernetic sense and is hence phenomenologically conscious.

So setting aside possible non-conscious subjects like state space vectors with causality, all subjects are phenomenologically conscious because they feed information about themselves back into themselves. But some do this in more interesting ways than others. For example, rocks are pretty boring. To the extent that we employ the fiction that they are “things” they mostly just react — behavior being the way we can detect experience in objects — to being part of the unfolding state of the universe. But some of that state is internal to the rock and interacts with itself over time so that, if nothing else, the rock maintains a stochastically stable molecular state for millennia. That hardly sounds like the kind of dynamic entities we think of as being the proper subject of cybernetics, but what’s interesting is that from a phenomenological complexity standpoint rocks are just as complex as more exciting systems, like trees.

Trees clearly respond to feedback: they grow by taking in water and sunlight, they stop growing when they reach the limit of their capabilities, and they recover from damage on their own. But rocks can grow by magnetism, nuclear forces, and gravity fusing them with other rocks, they may stop growing when there is no more stuff near by to glom on, and they can “repair” themselves by “preferring” more stable configurations. Sure, the epiphenomena or emergent behaviors of rocks are in an absolute sense less complex than those of trees because they require less information to describe, but they seem to be doing the same kinds of things at different scales.

We might say that rocks and trees are subjects in phenomenological tuples that are members of the same phenomenological complexity class, mirroring the terminology used in computer science to talk about groups of problems that can be solved by similarly complex abstract machines. Because rocks and trees — and clocks and many other things besides — are capable of having the same general sorts of experiences, we can imagine an abstract phenomenological subject capable of doing what any subject in this class is capable of, namely having direct experiences of reality. And if behaviorism were a complete accounting of animal psychology, this class would also include cats, dogs, and most importantly humans. But behaviorism is limited specifically because it doesn’t take into account the ways in which animals are not like trees by ignoring the experience of experience.

The experience of experience, or meta-experience, is much closer to what we think of everyday when we use the word “consciousness” than the phenomenological definition I’ve been using. It’s a capacity to experience and react not just directly to things in the world, but to experience and react to a subject’s own experiences of the world. Meta-experience is lacking in things like trees, but found in abundance in humans where it even makes possible the notion of subject and object in phenomenology, because without meta-experience there is no way to know that experience itself exists and thus no way to see the members of the subject, experience, object tuple. Because meta-experience allows this greater complexity of experience, we can see that it places a bound on the phenomenological complexity of “flat” subjects that directly experience reality without meta-experience. Thus we can think of rocks, trees, and the rest as forming our first phenomenological complexity class, the class of subjects with phenomenologically flat experiences.

We must then naturally ask, if meta-experience effectively bounds the phenomenological complexity of subjects with only flat experience, does something bound the phenomenological complexity of subjects with meta-experience? Unlike the jump from flat to meta-experience, there is no sense in which a subject can have meta-meta-experiences since those are still meta-experiences, so on the surface it seems this is the whole story. But just as deterministic Turing machines turn out to not to define the broadest computational complexity class, so too does meta-experience not define the extent of phenomenological complexity.

The additional complexity arises within meta-experience from the complexity of the meta-experience itself, in particular the complexity of the meta-experience of objects. Most of our knowledge about this comes from psychology because so far on Earth only neurons arranged into brains engage in meta-experience, though there is perhaps a case that some advanced artificial intelligence software achieves rudimentary meta-experience. And the complexity of how subjects meta-experience objects is exactly what Kegan explored in The Evolving Self.

But as already mentioned, we can’t simply point at Kegan’s work and say “quod erat demonstrandum” because it starts but doesn’t complete a bridge from humans to generic phenomenological subjects in meta-experiences. The group of meta-experiencing subjects is believed by many experts to include at least mammals and probably most tetrapods, cephalopods, and theoretical future strong AI, and a theory of phenomenological complexity classes needs to be applicable to all subjects. So we need to generalize from Kegan’s work on humans to include the full range of non-flat, meta-experiencing subjects.

In The Evolving Self, Kegan gives a taxonomy of 5 stages of human psychological development that can be identified in multiple ways. There is also an often unlisted sixth stage prior to the first, sometimes referred to as stage 0, that corresponds to a human’s early development from flat experiencing subject to meta-experiencing subject. Some ways Kegan and others have identified these stages, numbered 1 to 5, include

- Perceptive experience; impulsive action; minimal self narrative

- Concrete experience; deliberate action; other authored self narrative

- Abstract experience; planned action; socially authored self narrative

- Systematic experience; emergent action; self authored self narrative

- Dialectical experience; fluid action; self transforming self narrative

And with all due respect to Harvard University Press, Kegan himself gives a helpful chart summarizing the stages partway through In Over Our Heads:

The last column is especially relevant because it describes the structure of meaning-making, which is another way of talking about the phenomenological complexity of meta-experience. But Kegan is imprecise about what things like “categories” are and what it could mean to structure meaning making “across categories” because he has a background more founded in classics and continental philosophy than mathematics and analytical philosophy. So to give an accounting of phenomenological complexity classes more suited to my context within the rationalist community and executable philosophy, we need a more detailed approach to the phenomenological complexity at play in each stage in order to generalize them into phenomenological complexity classes.

Phenomenological Complexity Classes of Meta-experiencing Subjects

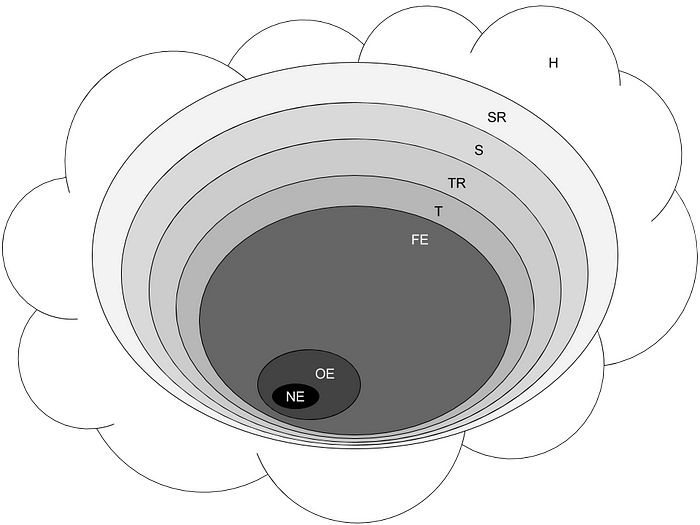

Taking Kegan’s stages as a rough guide, we can begin to explore the heights of phenomenological complexity within meta-experiencing subjects. Corresponding to each stage, we’ll look at the complexity classes of the phenomenological tuples of meta-experience, in particular the complexity of the object as meta-experienced by the subject to understand the capabilities and limitations of each complexity class. Because I find this to be a tricky subject to think about without a visual aid, we’ll work from left to right through the diagram below.

We’ve already covered flat experience, so moving directly into the meta-experience triangle depicted above, the first level of phenomenological meta-experience to consider corresponds to Kegan’s first stage and is the meta-experience of objects as things. This is in some sense the complexity you get for free from meta-experience because it’s naturally produced by meta-experience through experience of the {subject, experience, object} tuple — or more precisely the {subject, meta-experience, thing} tuple — where “thing” can be understood as the minimally complex way a subject can meta-experience an object. Things in this technical sense are irreducible, isolated, and filled with perceived essence because all ontology must be located within them by subjects with experiences in this complexity class since there is no where else for ontology to reside but as an inseparable part of the object itself.

Thing-level meta-experience forms a phenomenological complexity class by being the simplest expression of meta-experience while being bounded by the kinds of meta-experiences it doesn’t include. In particular, T — our shorthand for the set of thing-level meta-experience phenomenological tuples — can only use flat experience and meta-experience of things to experience the world, which leaves out any way to account for the experiences of other objects. As a simple example, a baby with thing-level meta-experience could experience a person and a ball but not experience a person looking at a ball because the person and ball are isolated and lack a means of experiencing each other from the baby’s perspective. To handle more complexity we must replace the category of things with a more complex structure.

In particular, a way is needed to include the phenomenological tuples of other subjects as objects of meta-experience. This is a very fancy way of saying we need things to have relationships, so we need to expand T to TR by allowing the inclusion of {subject, meta-experience, things-in-relationship} tuples. This is depicted in the meta-experience triangle as vertexes encircled by hyperedges, implicitly forming a hypergraph, in the “Thing Relationships” trapezoid.

Missing from thing-relationship-level meta-experience, though, is a way of experiencing the hypergraph itself rather than the vertexes and hyperedges within it. This matters because it misses the proverbial forest for the trees and gives the subject no way to meta-experience the whole beyond lumping it together again into an indivisible thing. This re-thing-ing of thing relationships is like the way cartoon trees merge into a unified forest as they recede into the background.

In order to maintain things and thing relationships simultaneously while zooming out we need a new level of complexity made possible by systems. A system is just a collection of things in relationships, but notably has a boundary at which we can talk about the system similarly to how we talk about things but without forgetting that the system is made up of things. Returning to the hypergraph, we can’t talk about the graphically invariant properties of a hypergraph, like connectivity, by only referencing the vertexes and hyperedges. We need to have a way of talking about what vertexes and hyperedges are in a hypergraph for the notion to make any sense. Thus a system is like a thing in that it is isolated but different in that it is reducible, creating opportunities for more complex ontology where essence may reside in the system rather than in the things in it.

This need is what gives rise to system-level meta-experience that expands the complexity class TR to S by including phenomenological tuples of the form {subject, meta-experience, things-in-relationships-in-system} or more simply {subject, meta-experience, system}. System-level meta-experience is what powers Kegan’s third stage and and offers complexity rich enough to capture many of the experiences of adults. In fact, from a cultural-historical perspective, most people who lived prior to the 16th century likely had experiences exclusively within S because the cultural expression of S is often referred to as the traditional, communal, or pre-modern worldview. This is especially interesting because the pre-modern worldview shows us the limits of system-level meta-experience because it is missing a key capacity that enables modern, systematic worldviews: relationships between systems.

Pre-modern thinking has no space for Other, and when a concept of Other is first acknowledged by a culture it is often as isolated systems with little to no interaction. As a culture develops towards modernism the people within it learn to reify systems into things so that systems can be put in thing relationships, but this gives up reducibility and remains fully expressible via the phenomenological tuples of S. Modernism proper arises when systems offering complete worldviews, usually defined by some “-ism” — scientism, communism, capitalism — compete to embody ontology. Fully engaging this competition requires systems not be reified into things to relate to each other but remain fully deconstructable within their relationships so that they can be compared in whole and in part. If no one system is found to be better than all others in all ways for all people, cultural post-modernism emerges to continue the search for truth by analyzing the relationships between systems.

Addressing culture like this is essential to understanding system-relationship-level meta-experience because culture is central to how humans experience system relationships. Outside of culture humans only seem to engage with system relationships in academic fields and confine that engagement to narrow slices of their total experiences. It’s only through culture that humans regularly need to meta-experience systems in relationship to one another and only when the culture is cosmopolitan enough to point to gaps in understanding that must be filled by system relationships. Thus culture and its development provides one of the few familiar examples of where the complexity of S is insufficient and must be extended to SR to include phenomenological tuples of the form {subject, meta-experience, things-in-relationships-in-systems-in-relationship} or {subject, meta-experience, systems-in-relationship}.

Given that system relationships are sufficient to experience the complexity of post-modernism, SR seems like it should be sufficient for all phenomenological tuples in which people might find themselves subjects. Yet within post-modernism there are hints that SR does not capture all possible phenomenological complexity since most people find post-modernism unsatisfying and it often causes them to adopt nihilistic world views. This suggests that using system relationships as ultimate ontological vehicles fails to completely resolve questions about the true nature of the universe, so there is likely more complexity needed to fully experience reality and construct a satisfying ontology of it.

We can overcome this failure by the same mechanism we used to go from thing relationships to systems by introducing an additional abstraction for holding systems together in relationships. We call this a holon, which is simply Greek for “whole” and follows Arthur Koestler’s use to mean something that is simultaneously a whole and a part. Unlike systems, holons can contain systems in relationships and things in relationships, so offer a way of talking about groupings of systems and their relationships without reifying systems into things. Thus holons are capable of holding repeatedly dividable systems of systems within a single context, enabling what is sometimes called a nebulous or fluid perspective. Here we refer to this as Holonic meta-experience, and it extends SR to H by including {subject, meta-experience, holon} phenomenological tuples.

The realm of holons in poorly explored. Kegan and Lahey’s research suggests less than 1% of adults reach stage 5, their equivalent to H, and those that do rarely do so before age 40, so the pool of potential investigators is small. Further, holons offer a way of forming what feels like, for humans, to be a complete world view and thus often gets mixed up in spiritual and religious language that is typically unwelcome in the very modern project of academic science and philosophy. That said, they are exciting for those same reasons and why much of my current thinking focuses on what I’ve termed holonic integration.

Holons may even capture all the complexity possible within meta-experience. To conclude with a little speculation, I suspect holons are likely enough to permit the inclusion of all possible phenomenological-tuples within our Tegmark Level I universe, aka our light cone or Hubble volume, by admitting only a single holon that covers all things, systems, and their relationships. Additional complexity may only be necessary to address theoretical cross-universe experiences and possibly their counterfactual instantiations in our universe. This is an active area of research for me, and one I hope to be able to address in the future.

Conclusions

Existentialist realist phenomenology permits an explanation of qualitative differences in experiences between subjects via the complexity of phenomenological tuples that subjects can be members of. The resultant complexity classes of phenomenological tuples start from non-experience (state space vectors without causality), outward experience (state space vectors with causality), and flat experience, then expand to include meta-experience and the increasing complexity of subjects’ meta-experiences of objects. Each class is a proper subset of the next, and they are in order

- NE (No Experience): {}

- OE (Outward Experience): NE + {subject, flat experience, object-that-is-not-subject}

- FE (Flat Experience): OE + {subject, flat experience, object}

- T (Thing-level meta-experience): FE + {subject, meta-experience, thing}

- TR (Thing-Relationship-level meta-experience): T + {subject, meta-experience, things-in-relationship}

- S (System-level meta-experience): TR + {subject, meta-experience, things-in-relationships-in-system}

- SR (System-Relationship meta-experience): S + {subject, meta-experience, things-in-relationships-in-systems-in-relationship}

- H (Holonic meta-experience): SR + {subject, meta-experience, holon}

Below, we graphically show the proper subset relationships and acknowledge that it is unclear if H is equal to the set of all possible meta-experiences, even if only within our Tegmark Level I universe.

This formulation of phenomenological complexity classes flirts at times with mathematical formalism, but the theory itself does not have a rigorous mathematical foundation. I am working to correct this, but perhaps unsurprisingly this is hard because it requires building a mathematical foundation of phenomenology. I don’t know when or if I will finish this project, but I am encouraged that others are also interested in and even tackling the problem, and yet others may be approaching the same problem from different perspectives.

There are also many applications of phenomenological complexity theory which I expect to explore given time: phenomenological complexity of ems, artificial intelligences, and animals; ways of increasing the phenomenological complexity of experiences subjects find themselves in; and comparative advantages of different phenomenological complexity classes within a subject’s teleology. I’ve already been doing this to some extent on this blog and in personal conversations without a unifying theory to power my thinking; now I have a hard core around which to build my ideas rather than letting them sit on a vast, interconnected web that few were willing to explore.

Thanks

Many people helped me to put this together, not only by supplying intellectual work to build upon, but by offering constructive feedback and additional phenomenological data as I worked out these ideas. The people who helped me, in no particular order, whether they knew it or not, not already named, include Olivia Shaefer, Jacob Czynski, Paul Christiano, Ben Hoffman, Lauren Horne, Tilia Bell, Eric Bruylant, Luke Muehlhauser, Anna Salamon, Duncan A Sabien, Mike Plotz, Sara Lynn Michener, Ryan Singer, David Malki !, ThunderPuff, Scott Alexander, Scott Aaronson, Kevin Simler, Andromeda Cohen, and my cat, Sammie. I apologize for anyone I forgot to mention; I exhausted the list of folks who were salient with no more than 5 minutes of thought.

2017–6–5 Update

I think it’s worth saying here that what I am pointing at with the meta-experience classes is a type-based approach to ontological complexity. Michael Commons has done the same, but in an eliminative approach rather than a phenomenological approach. I’ve now written a little about his ideas.